A Bunch of Words: an Introduction to SpaCy on CORD-19

Published:

Episode 1: Linguistic Features & Text Processing

Authors: Simone Azeglio, Marina Rizzi and Eugenio Tonanzi

Word Cloud based on words from CORD-19

Word Cloud based on words from CORD-19

Many valuable insights and information might be trapped in huge quantities of raw text, which are usually difficult to process in a smart manner: many words are rare, sometimes different words have almost the same meaning and, frequently, the same words in a different context or order can mean something completely different. To add a solid structure, and therefore useful information, it’s usually better to consider linguistic features. That’s exactly what spaCy is designed to do: extract quantitative information from text and let us play with it by coding. We’re going to see spaCy in action on COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19) from Allen Institute for AI, which is one of the best resources on the topic, prepared by the White House and a coalition of leading research groups.

With the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic, a huge number of academic articles related to it has been released. While this huge increase in the amount of research available can lead to a better understanding of the virus and its consequences, the great number of documents generated could be an obstacle in finding the best answer to some questions related to Covid-19. In this set of articles, we try to exploit techniques from Machine Learning and, in particular, from Natural Language Processing (NLP) in order to facilitate the process of information gathering and discovering. We are going to use the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19) from Allen Institute for AI, available from the Kaggle platform. The CORD-19 database is a resource of over 135,000 scholarly articles, including over 65,000 with full text, about COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, and related Coronaviruses. It is a freely available dataset, that was provided to the global research community in order to apply natural language processing techniques at the frontier, to generate new insights, suggestions and possible policy actions from the growing literature on coronavirus. As stated in the Kaggle website:

“There is a growing urgency for these approaches because of the rapid acceleration in new coronavirus literature, making it difficult for the medical research community to keep up”.

Starting from a sample

As a first step, we are going to set the environment and to download a tiny part of the dataset. In order to show step by step how the NLP techniques work, we will use only some sentences from an article of the dataset that we’ve already selected for you. We are going to explore the whole dataset in the next articles.

# Import the necessary libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import spacy

import json

# Load our sample file and take a look at it

path_to_sample = "sample.json"

input_file = open(path_to_sample)

with input_file as f:

data = json.load(f)

data['abstract']

We are interested in extracting sentences from this part of the .json file. Here is one sentence:

ex_sent0 = data['abstract'][0]['text']

print(ex_sent0)

Before starting our journey it’s right and proper to take a look at a few concepts from linguistics, in order to better understand how spaCy handles the processing of text data.

Linguistics 101: Dependency Grammars vs Phrase Structure Grammars

By using spaCy we’ll focus on analyzing sentence structures to identify patterns in word sequences. To understand sentence analysis and patterns, we’ll need some basic knowledge of linguistics. This paragraph contains a linguistic primer you can use as a reference.

By default, spaCy uses a dependency grammar rather than a phrase structure grammar, which is more commonly used in linguistics. Let’s delve into the difference between these two grammar types. If you haven’t a formal linguistic background, you may find this information helpful.

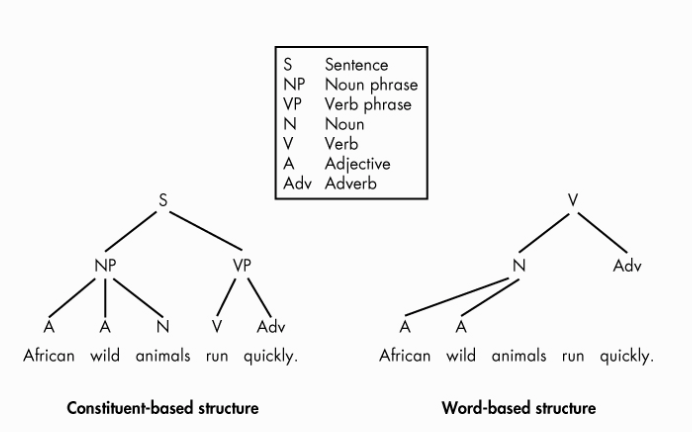

Also known as a constituent-based grammar, a phrase structure grammar models natural language based on how words combine to form constituents in a sentence. In syntax, a constituent is a group of words that works as a single unit in a sentence. Phrase structure rules decompose a sentence into its constituent parts, forming a tree structure that begins with individual words and builds up larger and larger constituents.

On the other side, a dependency grammar is a word-based grammar that focuses on the relations between individual words rather than between constituents. As a result, a dependency parse forms a tree that reflects how words relate to other words in a sentence.

The phrase structure tree breaks up the sentence based on the fact that the sentence consists of a noun phrase and a verb phrase. Those phrases appear on the second level of the hierarchy, directly under the sentence (S) mark — the formal top level. On the bottom level are the individual words that make up those phrases.

In contrast, the dependency structure uses the verb as the structural center of a sentence. The other words are either directly or indirectly connected to this verb with the help of directed links, known as dependencies. The dependency grammar that spaCy uses by default expresses the grammatical structure of a sentence as a set of one-to-one correspondences between words. Each of these relations represents a grammatical function in which one word is the child, or the dependent word, and the other is the head, or the governor. For example, in “green apple”, the dominant word is “apple”, and “green” is its subordinate. You can think of the head as the word with the most “relative importance” and without which the child doesn’t make sense.

Each word in a sentence must be connected to exactly one head. But the same word might have none, one, or several children. SpaCy’s grammar assumes that the head of a sentence (the Root token) is its own head. In the example we showed above (“African wild animals run quickly”), the verb “run” is the head of the sentence, so the head property of the Token object representing this word will refer to this same Token object.

Note that the head/child relationship has nothing to do with linear order in the sentence. For example, the child “wild” comes before its head “animals”, but the child “quickly” comes after its head “run”.

With this concepts in mind, we can now dive properly into spaCy’s processing pipeline, analyzing all the different tasks that are performed throughout the process.

Tokenization

Tokenization is the task of splitting a text into meaningful segments, called tokens. A token is everything we can find in our text: a word, a piece of punctuation, a number, a symbol. The input required is a unicode text, and the output is a spaCy’s Doc object.

The key principle is that spaCy’s tokenization is non-destructive, which means that we will always be able to reconstruct the original input from the tokenized output. Whitespace information is preserved and no information is added or removed during the process.

But how tokenization really works? The answer is that it works by applying rules that are specific to each language. For example, the english word “don’t” should be split into two tokens representing its meaning, “do” and “n’t” (not), while the acronym “U.K.” should always remain one token. However, if punctuation comes at the end of a sentence it should always be split off to be a token on its own. Generalizing this example, spaCy’s tokenizer proceeds in two steps. First, the raw text is split in substrings on whitespace characters. Then, each substring is processed, from left to right, checking the following questions:

- Does the substring match a language-specific rule?

- Can a prefix, suffix, infix or piece of punctuation be split off?

If there’s a match, the rule is applied and the tokenizer continues its loop. In this way, spaCy can also deal with nested tokens like combinations of abbreviations and multiple punctuation marks.

Needless to say, each and every language has plenty of its own grammar and semantic mechanics, and this is why each language that is supported by spaCy has its own subclass, that loads in lists of hard-coded data and rules.

We can now proceed to tokenize our sample text extracted before:

# Load English language

nlp = spacy.load(“en_core_web_sm”)

# Tokenize the text

doc = nlp(ex_sent0)

# Collect the information in a nice-looking Pandas DataFrame

tokens_list = np.array([token for token in doc])

tokens_table = pd.DataFrame(tokens_list, columns = ["Token"])

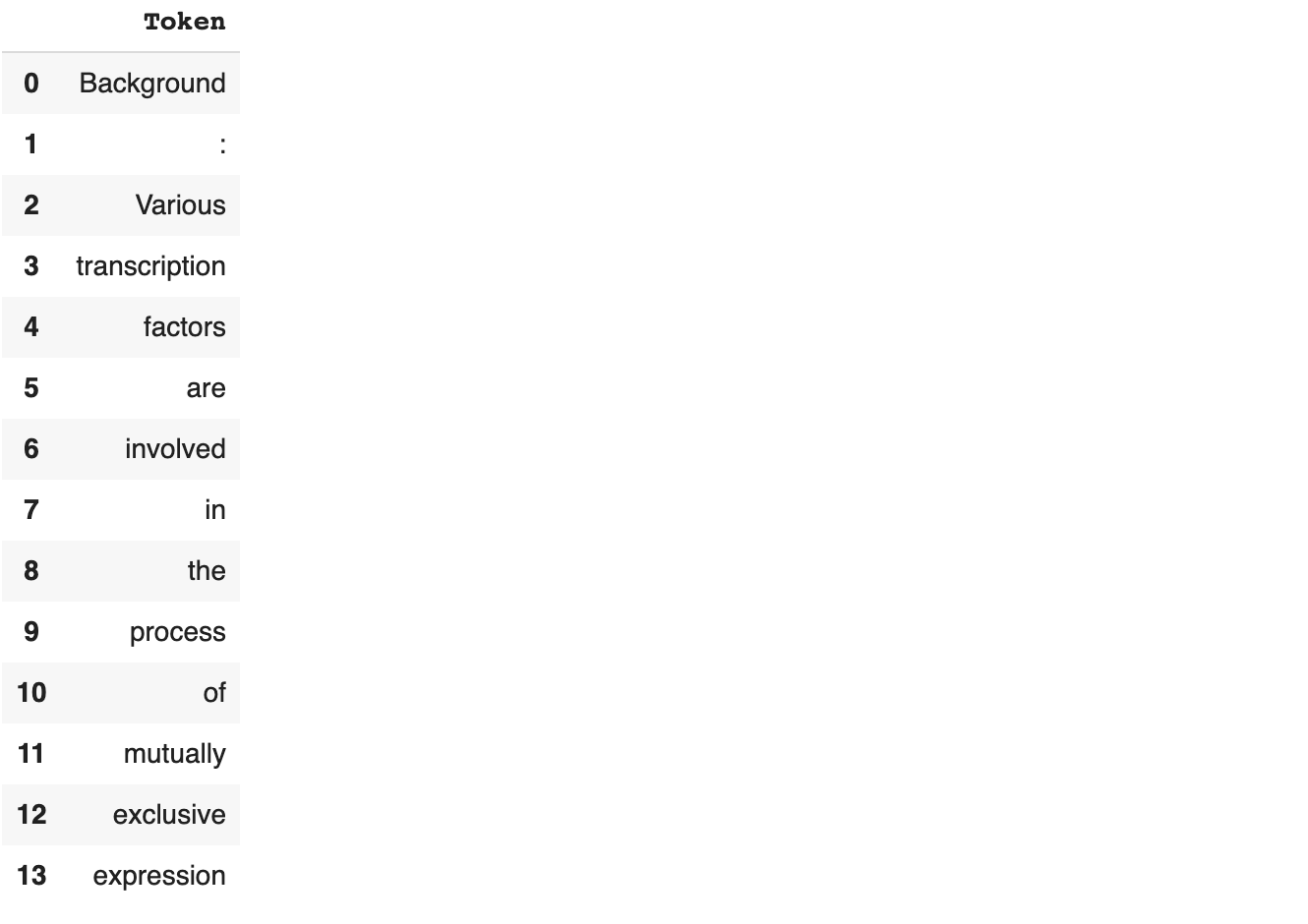

tokens_table.head(14)

Moreover, spaCy also allows its users to define custom tokenization rules, and to manually build and/or modify the tokenizer or the tokenization output. As you can imagine the possibilities are countless, so please check our references if you’re interested in more details.

Lemmatization

Our text has now become a collection of tokens, and we’re getting closer to a representation that can allow us to do statistics on it. But we still need to deal with a couple of problems.

First of all, we need to identify together words with different representations but the same meaning. For example, “walking” and “walks” are two different tokens and in principle, they should be treated as different words. However, when analyzing a text, we don’t really want to consider them as different entities, but rather as different expressions of the same word, the verb “walk”.

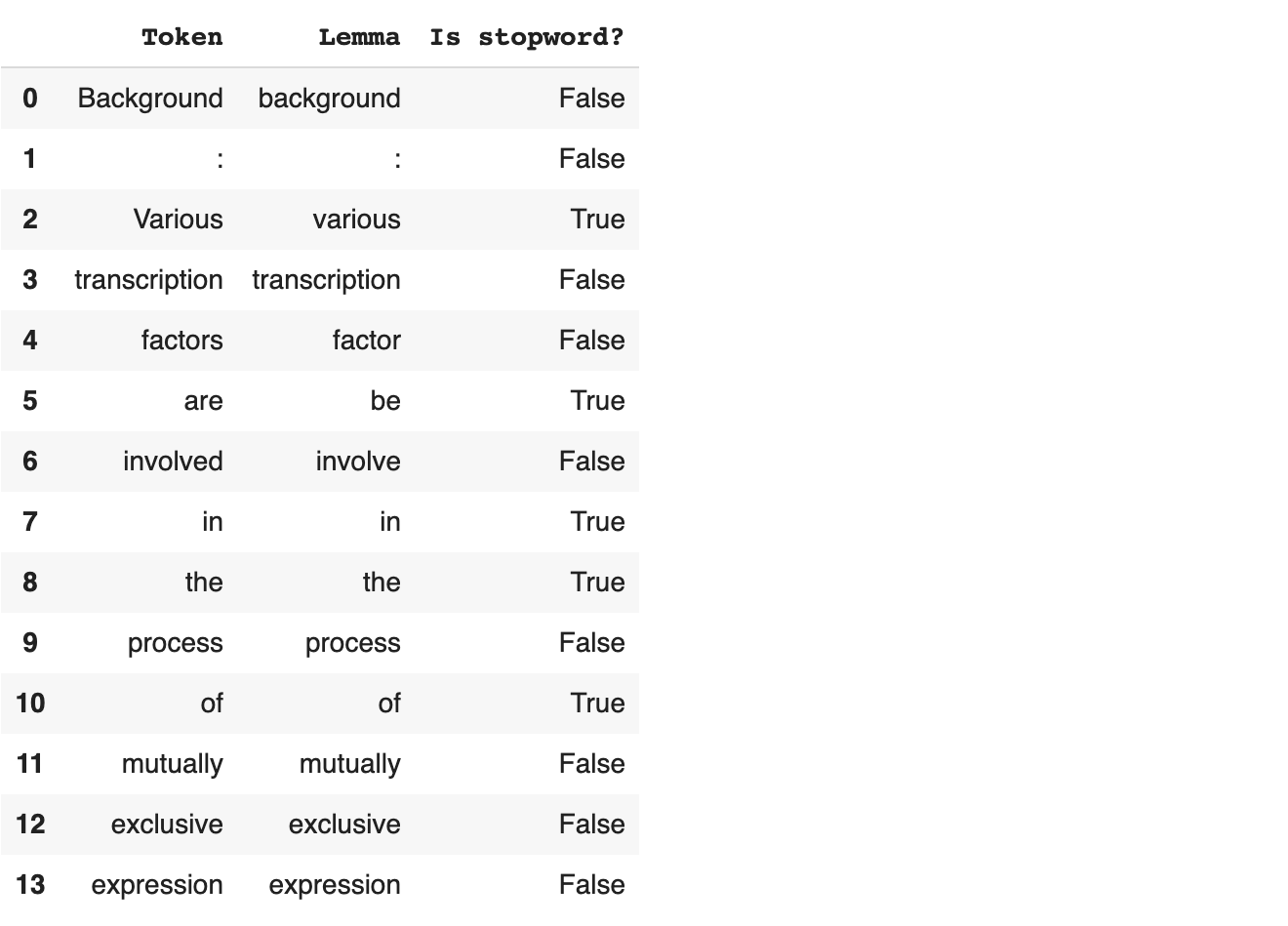

Lemmatization is the process of reducing the inflected forms of a word to their root form so that they can be analyzed as a single item, identified by the word’s lemma, or dictionary form. As was the case for the tokenizer, this procedure strongly depends on the language at hand. Usually, a dictionary for the selected language is loaded, and lemmatization is performed by dictionary lookup, with the addition of several hand-crafted rules.

Last but not least, we want to distinguish between words that can provide us some information about the text and non-informative words, also called stopwords. For example, every text is usually full of articles, conjunctions, pronouns, auxiliary verbs and so on. However, we cannot expect to extract much information from this kind of words, because they are building blocks of pretty much every sentence in every text. This is why sometimes they need to be kept separated from “real” words. Fortunately, spaCy’s tokenizer does this job for us while splitting the text, and we can recover the features discussed so far by making use of the token.lemma_ and token.is_stop attributes.

lemmas_list = np.array([[token, token.lemma_, token.is_stop] for token in doc])

lemmas_table = pd.DataFrame(lemmas, columns = ["Token", "Lemma", "Is stopword?"])

lemmas_table.head(14)

So far so good, we are now left with a more schematic version of our starting text, that now results segmented into all its words. This can be considered the starting point for building and applying NLP algorithms and machine learning.

Part-of-speech Tagging

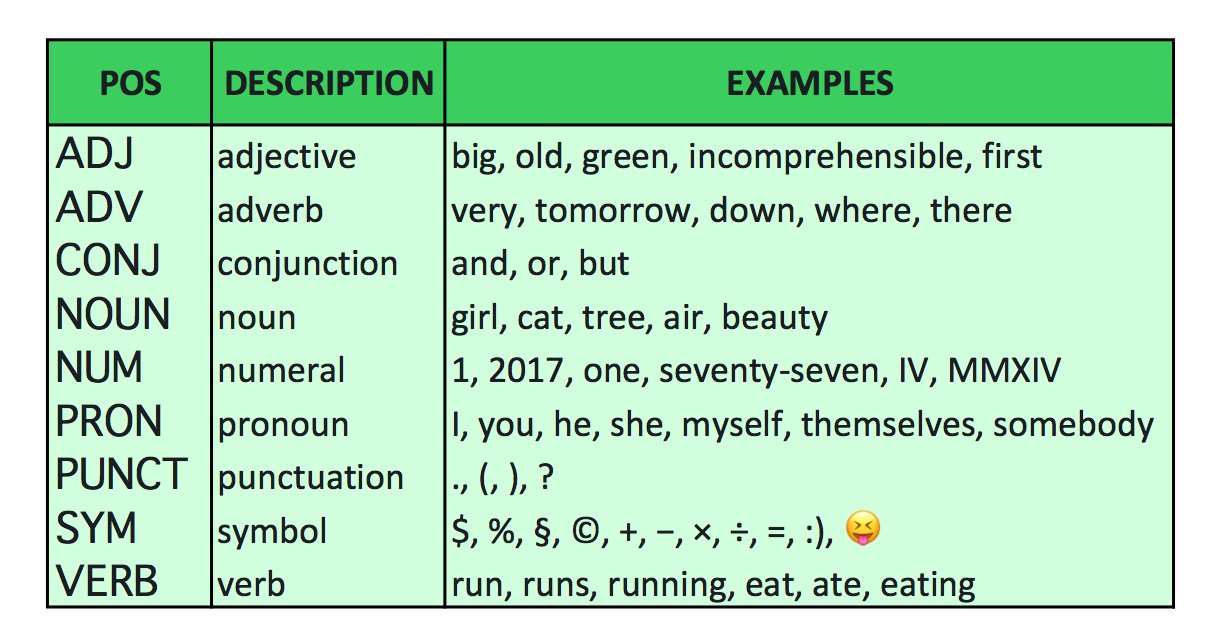

After tokenization and lemmatization, the next phase for word processing is part-of-speech (POS) tagging. Part-of-Speech tagging is the process through which we assign to each token a label that describes the part of speech (such as noun, verb, and so on) the token represents. Here is where the statistical model comes in.

SpaCy makes predictions about which tag or label is the most appropriate for a word using neural network models.

After the model is trained with a good number of examples, it is able to make predictions for each word. SpaCy makes available some pre-trained models for each language, that are already usable on text documents. Note that each trained model is generalizable only within the specific language for which it was trained since the tag prediction relies on rules that are language-specific. For example, in English, a word following “the” is very likely a noun, but this rule is not generalizable to other languages like Spanish or Italian. Some of the POS tags are the following ones:

Some POS Tagging, available from spaCy documentation: https://spacy.io/api/annotation#pos-tagging

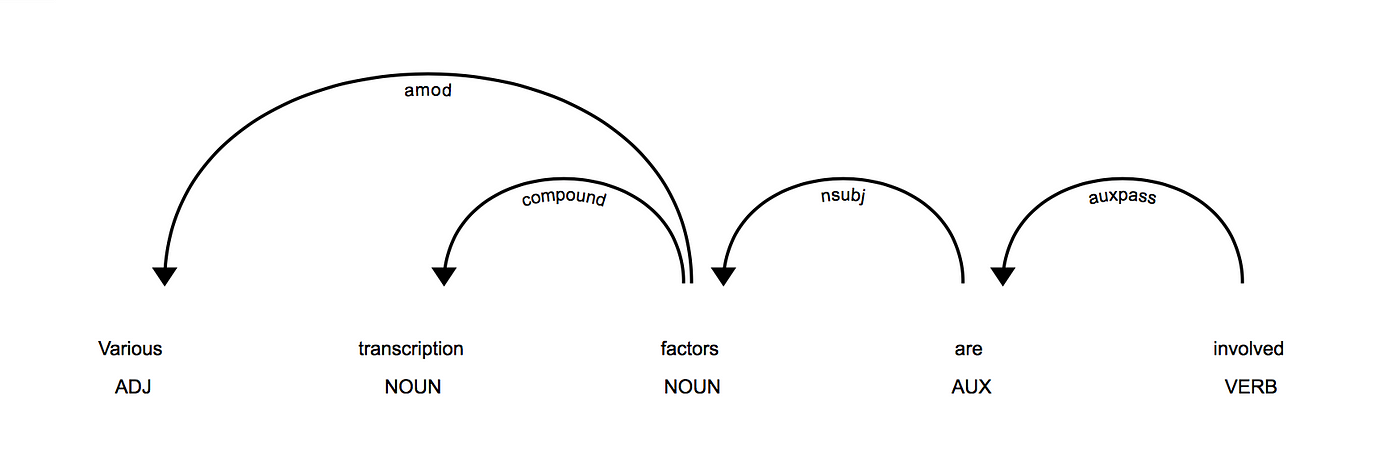

Together with this, the model is also able to trace back the dependency parse tree structure in our sentence, giving each word its position. The following image is obtained using the “Visualizer” feature, available with SpaCy:

An example of a structure that represents the “parse dependency”, the dependency between words.

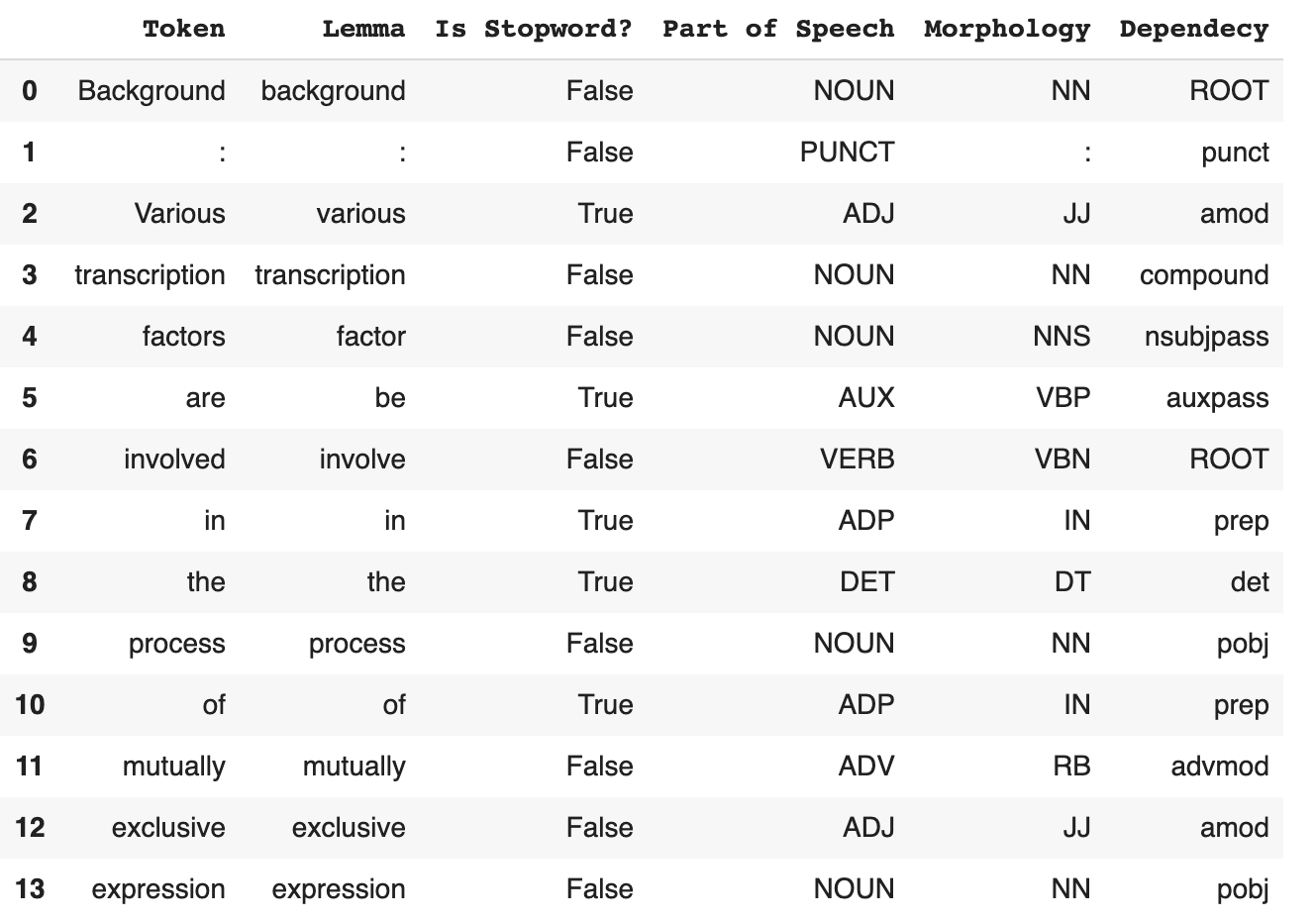

Now let’s apply POS tagging on the example sentence we already extract.

words_list = np.array([[token, token.lemma_, token.is_stop, token.pos_, token.tag_, token.dep_, ] for token in docx])

words_table = pd.DataFrame(words_list, columns = [“Token”, “Lemma”, “Is Stopword?”, “Part of Speech”, “Morphology”, “Dependecy”])

words_table.head(14)

The fifth column is the one we haven’t already discussed. It indicates the Morphological Tag of the considered word. The difference between the Part-of-Speech Tag and the Morphological Tag is that the Morphological Tag code not only the word type (verb, noun, etc), but also other characteristics like whether the word is singular or plural, or for verbs what is the tense.

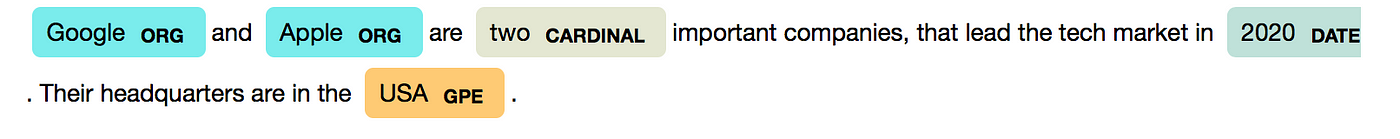

Named Entity Recognition

Another interesting feature of SpaCy is that it is also able to recognize which type of “object” are some entities (for example, that “Apple” is a company or an institution, that the “U.K” is a geopolitical entity, that “1$ billion” is a monetary value, that 2007 is a date, and so on).

It is also possible to add arbitrary classes to the entity recognition system, and consequently update the model with new examples. It is important to note that the entity recognition feature strongly relies on the examples it was trained on, and so it could be that it does not always work perfectly. In this case, some tuning and adjustment could be needed afterward, in order to adjust the entity recognition to the context of the document analyzed.

Here there is an example in which the SpaCy visualizer is used in order to recognize different entities, that are highlighted and labeled with a short sequence of characters, which represent the category the words belong to.

Example of Named Entity Recognition, using the VIsualizer provided by SpaCy.

Language Processing Pipelines

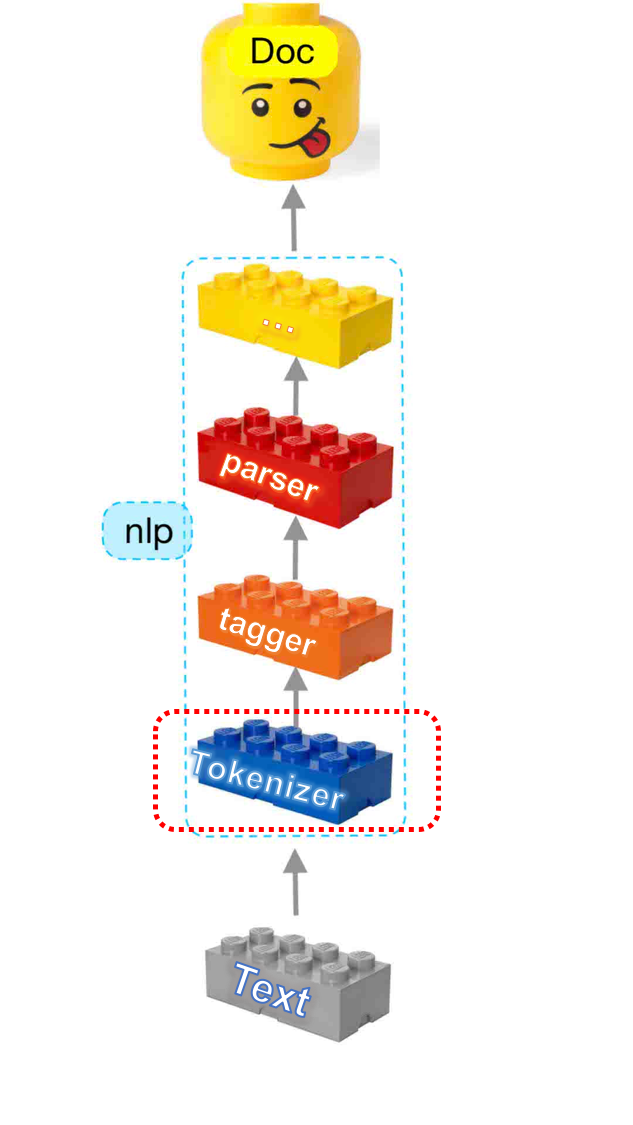

We have unleashed spaCy’s power, which enables us to recover many information and structure from text documents. The features we saw are the first bricks to construct our journey in the world of Natural Language Processing, applying these techniques in the CORD-19 dataset. However, we would like to understand if it’s possible to automate some processes and build some kind of pipeline.

Every operation — on text — that we have seen so far can be thought of as a LEGO brick itself. We want to pile bricks up and build a re-usable construction: luckily, we are not left alone since, at spaCy, developers have built everything in a modular way, with the idea of sequentializing every operation.

spaCy’s language processing pipeline

spaCy’s language processing pipeline

The default pipeline consists of a tagger, a parser, and an entity recognizer. Each of these components returns the processed Doc, which is then passed on to the next component. As a result, our initial raw text becomes split into a series of tokens, each one associated with its tags and its role in the dependency parse tree, as we saw in the last table presented above.

It is also possible to design a custom pipeline, which of course, always depends on the statistical model we are considering.

In this way, we should take heed to the fact that the Tokenizer is considered as a “special” component and isn’t part of the regular pipeline. The technical rigidity here is that there can be only one tokenizer, and while all other pipeline components take a Doc and return it, the tokenizer takes a string of text and turns it into a Doc.You can still customize the tokenizer, though: nlp.tokenizer is writable, so you can either create your own [Tokenizer](https://spacy.io/usage/linguistic-features#native-tokenizers) class from scratch or even replace it with an entirely custom function.

We’ve kinda understood how to compose different operations but: it’s time to see how to process text.

Text Processing

Let’s go back to our sample, extracted from one of the articles from CORD-19. We are pretending to have a huge amount of text to process, when processing large volumes of text, these models are more efficient if you let them work on batches of texts. nlp.pipe method takes an iterable of text and yields processed Doc objects. In this way, the batching is done internally.

Firstly, we can extract a few other sentences from the abstract of the selected article:

# 2 more sentences

ex_sent1 = data['abstract'][1]['text']

ex_sent2 = data['abstract'][2]['text']

# Building texts list

texts = [ex_sent0, ex_sent1, ex_sent2]

# Building docs in this way is efficient

docs = list(nlp.pipe(texts))

For a further in-depth analysis of spaCy’s nlp.pipe method, you can take a look at the official documentation, which is definitely exhaustive.

Let’s take a look at what we get by using the entity linking feature, since we only want entity identifiers, we can remove LEGO bricks with the disable parameter. Our construction is even dynamic and customizable:

for doc in nlp.pipe(texts, disable=["tagger", "parser"]):

print([(ent.text, ent.label_) for ent in doc.ents])

It apparently works but by deeply analyzing each term we see some incongruences. This is a much more serious problem than it seems and it’s related to the fact that scientific terms are not statistically significant in a “regular English” sentence. You can reproduce this code with some non-scientific sentence and you’ll see that everything works fine. How do we get along with scientific articles though? Luckily NLP researchers have worked out some solutions, in the next few articles we are going to pave the way for more complicated language models such as BERT and specifically SciBERT which deals way better with scientific terms.

Conclusions

In this short introductory article, you’ve taken a sip of the very NLP basis with SpaCy. The road to coming is still long and winding, but we’re preparing some more tutorials for you so that you can drive through nicely and easily. Take your time to practice with SpaCy — and this dataset — and stay tuned for further updates.

References:

- Dead Code Should Be Buried, M. Honnibal

- Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing, C. D. Manning & H. Schuetze

- The Handbook of Computational Linguistics and Natural Language Processing, A. Clark, C. Fox & S. Lappin

- SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text, I. Beltagy et al

- Natural Language Processing and Computational Linguistics, B. Srinivasa-Desikan